Biography

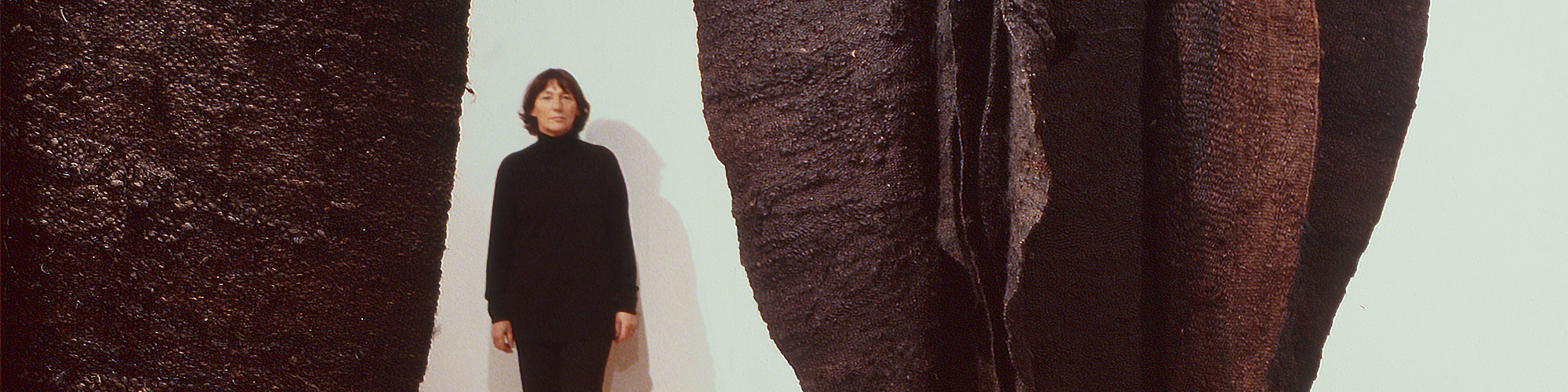

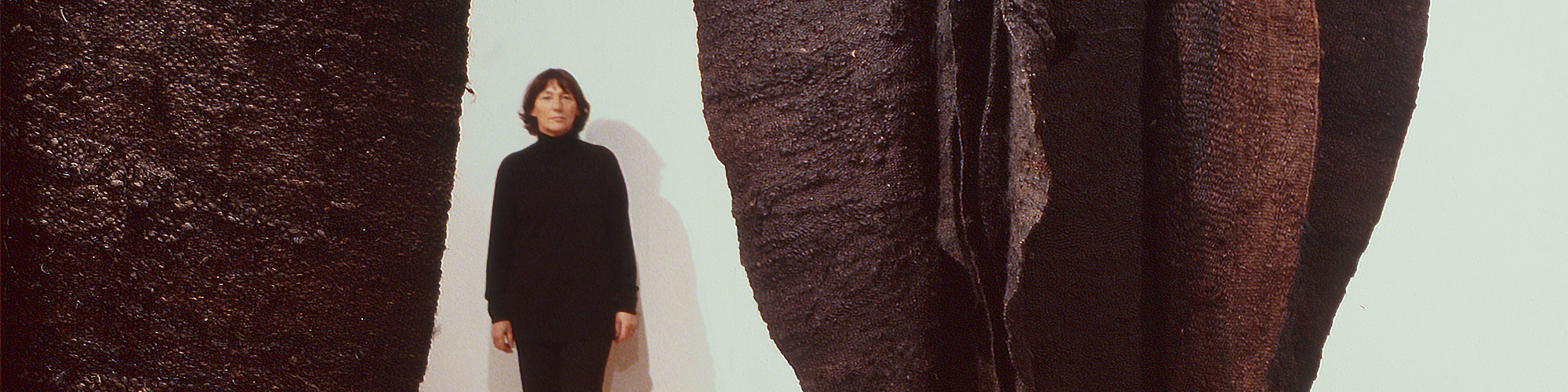

Magdalena Abakanowicz is a sculptural artist who has had a lasting impact on the art world with her revolutionary concept of textile art and sculpture as interpretation of life, inspiring and opening up new possibilities. She’s one of the most acclaimed figures of Polish art in the world.

Born Marta Abakanowicz in 1930, she was one of two daughters of an aristocratic family with Polish-Russian-Tatar roots. Her mother Helena Domaszowska came from a noble background and her father, Konstanty, was part Polish, part Russian and part Tatar, son of a general of Tsar Nicholas II’s army. During the Russian Revolution he attended a military school. Initially, the family lived at Falenty, municipality of Raszyn near Warsaw. When Magdalena was one year old, her family moved from Falenty to an estate located in Krępa, Garwolin municipality, also near Warsaw. In 1943, Magdalena’s mother lost her arm during a shootout and aggressive behaviour of Nazi soldiers, and in 1944 the whole family had to flee before the arrival of Soviet troops, irretrievably losing all their possessions and privileges. These events had an impact on Magdalena’s imagination, forming the ground for her reflections as well as a theme of her adult work.

In 1945 the Abakanowicz family moved to Tczew, Pomerania, where Magdalena attended secondary school. In 1949, she graduated from the Public High School of Visual Arts in Gdynia and went on to study at the National College of Fine Arts in Sopot (PWSSP), moving to the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw the following year. She obtained her diploma in painting with a focus on tapestry in 1954. As a student, she already began to develop her own artistic language, initially by painting on fabric and then, increasingly bold in her use of the weaving technique, developing her own material to produce monumental soft sculptures. To weave those structures and forms, she used sisal thread, horse hair or wool, among other materials. In 1956 Abakanowicz married Jan Kosmowski, an engineer with whom she spent the rest of her life. Her first solo exhibition took place at the Kordegarda Gallery in Warsaw in 1960, where the artist presented painted fabrics with floral and zoomorphic compositions. Even these early works exhibit the artist’s fascination with nature, mystery, and monumentalism that came to be so characteristic of her later works.

The year 1962 marked Abakanowicz’s debut as a sculptor at the Lausanne International Tapestry Biennial where she presented her Composition of White Forms, a tapestry that was noticed and appreciated both by the jury and critics from many countries. Since then, she participated in all subsequent editions of the Biennials until 1985. In 1963, Magdalena Abakanowicz was invited by Wiesław Borowski to prepare a solo exhibition at the Gallery of Modern Art in Warsaw. The exhibition featured new woven works in increasingly large formats (2x3 or 3x5 metres). It was at that time that they became known as ‘Abakans’. The term has since been used to describe all of Magdalena Abakanowicz’s spatial textile works. In 1965 Abakanowicz won a gold medal in functional art at the São Paulo Art Biennial, which firmly established her work in the field of innovative world art. Her Abakans, which are monumental, three-dimensional installations made of artistic fabric, were hailed as a revolution in textiles as well as in sculpture. They created an independent space, their soft form, their arrangement, their texture and their scent allowing a close, indeed intimate, contact with the work. In 1965, Magdalena Abakanowicz took part in the First Biennial of Spatial Forms in Elbląg, where she left her first large-scale sculpture in a public space as a forerunner of her later similar creations.

In 1965, she organised a team to collaborate on the weaving of abakans, and in 1966 she moved to a studio at 16 Stanów Zjednoczonych Ave., Warsaw. The 1960s and 1970s saw the artist’s impressive activity in creating woven works and showing them to the world. During this time, she alternated between series of large single Abakans, extensive installations of fabric compositions, as well as series of tapestries and weavings that were smaller in size but elaborate in structure and space. The artist treated each exhibition as a piece of art in its own right. The works that made up the exhibitions were alive in their own way, they transformed depending on the particularities of space, lighting or arrangement, each time giving the space a revealing new quality, appropriating it. While appearing each time as a new whole, they would always carry a universal message. That is why Magdalena Abakanowicz creations retain their truth and authenticity in any place of the world.

An important artistic decision in the early 1970s was to introduce ship lines into the exhibition, powerful ropes that further stretched the structure and fabric of the installation, extending beyond its structure. It was at that time that her imaginary of memories and childhood began to evolve into a fascination with biological force to later lead the artist towards existential reflection, looking closely at the individual.

During the 1970s and 1980s, the artist progressed towards an interpretation of the human being as an entity linked to nature, but also irresistant to destructive forces. This evolution can be seen in the huge contrast between the first stage that the Abakans were and the developing new areas of exploration. On the one hand, the abundance of structures, the sensuality of soft fabrics and, on the other, broken shells, baggy figures made of sackcloth, torsos, heads, nests of obtuse shapes reminiscent of cocoons or eggs. It is the time when she began to work on figural and non-figural works that were given the general title Alterations, which included Heads, Sitting Figures, Backs and Embryology. Abakanowicz created all those series almost in parallel, alternating and repeating the scale and proportions. The proportions of the works vary, just as the groups vary in number: the most numerous Embryology consists of several hundred pieces. And just as with the Abakans before, the artist filled the spaces with groups of figures or signs, all the while answering her own most essential and personal questions.

Between 1976 and 1980, Backs were created, a series of eighty representations of the human torso, varying in structure and proportion. A few years later, between 1986 and 1987, a series of sculptures entitled The Crowd was created. The figures represented were now standing, with the individual portrayed as a naked, unprotected human exposed to manipulation and oppression. In the meantime, the sculptor also returned to work on organic structures, the best known of which is the Embryology series, consisting of dozens of egg-like soft lumps of various sizes, scattered around the exhibition hall of the Polish Pavilion at the 1980 Venice Biennale. At the end of the 1980s and in early 1990s, the artist once again changed the material of her sculptures, beginning to increasingly employ metals and alloys such as bronze, as well as wood, stone and clay. In the 1980s, Magdalena Abakanowicz was responding to the political changes taking place in Poland and the onset of a period of reform connected with the arisal of Solidarity trade union. When the progress of change was halted by martial law in 1981, the artist responded by placing one of her headless bodies in a wooden Cage.

In 1985, the artist produced Katarsis, a multi-figure outdoor composition. Thirty-three monumental figures stood in the open space of the Spazi d'Arte Park in a private estate of Giuliano Gori, in Fattoria di Celle, near Pistoia, Italy. It was the first set of sculptures intended for an open space, cast in bronze. The naked bodies devoid of identity fused with the nature around, creating a sensitising space for contemplation. The forms of the Katarsis and their positioning are suggestive of a religious ritual, a form of saying goodbye to a certain stage, of purification, of renewal. This is the first time Magdalena Abakanowicz realised such a magnificent work in bronze, deliberately assuring its longevity through the material chosen. In 1987, Abakanowicz made an installation of seven stone circles, each 280 cm in diameter. The artist set the circles on a hill in the Billy Rose Scultpure Garden at the Israel Museum, Jerusalem. The name of the Negev installation comes from the desert where the artist found the giant boulders needed for the work. The white, unevenly positioned round stones, almost three metres in diameter, invite the viewer to come between them and, by restricting visibility, squeezing the space, they somehow provoke the viewer to touch the rough surfaces, they compel direct contact. Following the spectacular impact of that installation, the artist created another monumental composition in 1988, in an open space in Seoul, Republic of Korea. Invited to the International Open Air Sculpture Symposium – a side event to the Seoul Olympic Games – she created there 10 huge, metaphorical animal heads in a composition called Space of the Dragon. In 1993, the Space of Becalmed Beings is created – a group of 40 figures of Backs cast in bronze and personally set up by the artist in the sculpture garden of the City Museum of Contemporary Art in Hiroshima. On the hill that was the last refuge of the survivors of the atomic blast, the artist placed objects that, as in Katarsis, collectively became a symbol and as it were a ritual of farewell and hope at the same time.

Abakanowicz continued to create further large-scale bronze sculptures, as well as the Incarnations series from 1985-1987. Incarnations, followed by Anonymous Portraits, are several dozen self-portraits and animal heads. From the beginning of her creative activity, Abakanowicz has asserted her unity with nature and her special relationship to trees as a sign and symbol of life and continuity. However, it was not until 1981 that she created her first works carved from tree logs entitled Trunks, followed in 1987-89 by a series named War Games, featuring symbols of life and death, strength and weakness made from fallen, hewn and abandoned tree trunks. She gives them the appearance of living beings, banding them with metal clamps, protecting them with canvas and jute, fixing them and making their existence meaningful by virtue of her attention. The constant need to explore new materials led Magdalena Abakanowicz to take on glass in her two series Sarcophagi and Glass Houses, created during her stay in France in 1983. The artist's versatile and open creative mind earned her an invitation to compete in 1991 for an urban design of extension of the grand axis of Paris at La Défense. The tree as a symbol of life was used to create the Arboreal Architecture project, extremely humanistic in its message and innovative in its engineering. Her idea envisaged the construction of monumental tree-shaped buildings, the interiors of which were to serve residential and commercial functions, while the exteriors were to become living, green structures. The concept of Arboreal Architecture was further developed, or perhaps echoed, in Hand-like Trees (1992-1993). Cast in bronze the size of natural trees, they were set up by the artist in urban spaces.

Metaphorical animal figures created at the same time as a continuation and development of the Heads series, corresponding with the human groups/herds, clearly and friendly relate to the human figures. The use of the same material seems to emphasise the unity and coherence of all co-existing living beings on earth. The artist gives the human figures animal heads, as if symbolically developing the idea of the two working together, complementing human weakness and fragility with animal strength. The power resides in unity.

Simultaneously, the sculptor continued the human theme, changing the material. Between 1990 and 1991, the Bronze Crowd was created. The artist’s last major project is Agora, a composition of 106 similarly shaped giant cast iron figures in motion forming a dynamic walking crowd. The surfaces of individual figures are reminiscent of tree bark or wrinkled skin, seemingly similar and anonymous, but different, each having its own distinct character. The group was placed in Chicago’s Grant Park.

Magdalena Abakanowicz died on 20 April 2017, leaving behind a unique body of work – a testimony to the events of the 20th century, wars, political and social abuses and, in this context, people's struggles and determination to pursue their dreams. And yet, her work has the power of a universal message, with a visionary outlook into the future, pointing to solutions and answers to humanity's most vital questions.

Born Marta Abakanowicz in 1930, she was one of two daughters of an aristocratic family with Polish-Russian-Tatar roots. Her mother Helena Domaszowska came from a noble background and her father, Konstanty, was part Polish, part Russian and part Tatar, son of a general of Tsar Nicholas II’s army. During the Russian Revolution he attended a military school. Initially, the family lived at Falenty, municipality of Raszyn near Warsaw. When Magdalena was one year old, her family moved from Falenty to an estate located in Krępa, Garwolin municipality, also near Warsaw. In 1943, Magdalena’s mother lost her arm during a shootout and aggressive behaviour of Nazi soldiers, and in 1944 the whole family had to flee before the arrival of Soviet troops, irretrievably losing all their possessions and privileges. These events had an impact on Magdalena’s imagination, forming the ground for her reflections as well as a theme of her adult work.

In 1945 the Abakanowicz family moved to Tczew, Pomerania, where Magdalena attended secondary school. In 1949, she graduated from the Public High School of Visual Arts in Gdynia and went on to study at the National College of Fine Arts in Sopot (PWSSP), moving to the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw the following year. She obtained her diploma in painting with a focus on tapestry in 1954. As a student, she already began to develop her own artistic language, initially by painting on fabric and then, increasingly bold in her use of the weaving technique, developing her own material to produce monumental soft sculptures. To weave those structures and forms, she used sisal thread, horse hair or wool, among other materials. In 1956 Abakanowicz married Jan Kosmowski, an engineer with whom she spent the rest of her life. Her first solo exhibition took place at the Kordegarda Gallery in Warsaw in 1960, where the artist presented painted fabrics with floral and zoomorphic compositions. Even these early works exhibit the artist’s fascination with nature, mystery, and monumentalism that came to be so characteristic of her later works.

The year 1962 marked Abakanowicz’s debut as a sculptor at the Lausanne International Tapestry Biennial where she presented her Composition of White Forms, a tapestry that was noticed and appreciated both by the jury and critics from many countries. Since then, she participated in all subsequent editions of the Biennials until 1985. In 1963, Magdalena Abakanowicz was invited by Wiesław Borowski to prepare a solo exhibition at the Gallery of Modern Art in Warsaw. The exhibition featured new woven works in increasingly large formats (2x3 or 3x5 metres). It was at that time that they became known as ‘Abakans’. The term has since been used to describe all of Magdalena Abakanowicz’s spatial textile works. In 1965 Abakanowicz won a gold medal in functional art at the São Paulo Art Biennial, which firmly established her work in the field of innovative world art. Her Abakans, which are monumental, three-dimensional installations made of artistic fabric, were hailed as a revolution in textiles as well as in sculpture. They created an independent space, their soft form, their arrangement, their texture and their scent allowing a close, indeed intimate, contact with the work. In 1965, Magdalena Abakanowicz took part in the First Biennial of Spatial Forms in Elbląg, where she left her first large-scale sculpture in a public space as a forerunner of her later similar creations.

In 1965, she organised a team to collaborate on the weaving of abakans, and in 1966 she moved to a studio at 16 Stanów Zjednoczonych Ave., Warsaw. The 1960s and 1970s saw the artist’s impressive activity in creating woven works and showing them to the world. During this time, she alternated between series of large single Abakans, extensive installations of fabric compositions, as well as series of tapestries and weavings that were smaller in size but elaborate in structure and space. The artist treated each exhibition as a piece of art in its own right. The works that made up the exhibitions were alive in their own way, they transformed depending on the particularities of space, lighting or arrangement, each time giving the space a revealing new quality, appropriating it. While appearing each time as a new whole, they would always carry a universal message. That is why Magdalena Abakanowicz creations retain their truth and authenticity in any place of the world.

An important artistic decision in the early 1970s was to introduce ship lines into the exhibition, powerful ropes that further stretched the structure and fabric of the installation, extending beyond its structure. It was at that time that her imaginary of memories and childhood began to evolve into a fascination with biological force to later lead the artist towards existential reflection, looking closely at the individual.

During the 1970s and 1980s, the artist progressed towards an interpretation of the human being as an entity linked to nature, but also irresistant to destructive forces. This evolution can be seen in the huge contrast between the first stage that the Abakans were and the developing new areas of exploration. On the one hand, the abundance of structures, the sensuality of soft fabrics and, on the other, broken shells, baggy figures made of sackcloth, torsos, heads, nests of obtuse shapes reminiscent of cocoons or eggs. It is the time when she began to work on figural and non-figural works that were given the general title Alterations, which included Heads, Sitting Figures, Backs and Embryology. Abakanowicz created all those series almost in parallel, alternating and repeating the scale and proportions. The proportions of the works vary, just as the groups vary in number: the most numerous Embryology consists of several hundred pieces. And just as with the Abakans before, the artist filled the spaces with groups of figures or signs, all the while answering her own most essential and personal questions.

Between 1976 and 1980, Backs were created, a series of eighty representations of the human torso, varying in structure and proportion. A few years later, between 1986 and 1987, a series of sculptures entitled The Crowd was created. The figures represented were now standing, with the individual portrayed as a naked, unprotected human exposed to manipulation and oppression. In the meantime, the sculptor also returned to work on organic structures, the best known of which is the Embryology series, consisting of dozens of egg-like soft lumps of various sizes, scattered around the exhibition hall of the Polish Pavilion at the 1980 Venice Biennale. At the end of the 1980s and in early 1990s, the artist once again changed the material of her sculptures, beginning to increasingly employ metals and alloys such as bronze, as well as wood, stone and clay. In the 1980s, Magdalena Abakanowicz was responding to the political changes taking place in Poland and the onset of a period of reform connected with the arisal of Solidarity trade union. When the progress of change was halted by martial law in 1981, the artist responded by placing one of her headless bodies in a wooden Cage.

In 1985, the artist produced Katarsis, a multi-figure outdoor composition. Thirty-three monumental figures stood in the open space of the Spazi d'Arte Park in a private estate of Giuliano Gori, in Fattoria di Celle, near Pistoia, Italy. It was the first set of sculptures intended for an open space, cast in bronze. The naked bodies devoid of identity fused with the nature around, creating a sensitising space for contemplation. The forms of the Katarsis and their positioning are suggestive of a religious ritual, a form of saying goodbye to a certain stage, of purification, of renewal. This is the first time Magdalena Abakanowicz realised such a magnificent work in bronze, deliberately assuring its longevity through the material chosen. In 1987, Abakanowicz made an installation of seven stone circles, each 280 cm in diameter. The artist set the circles on a hill in the Billy Rose Scultpure Garden at the Israel Museum, Jerusalem. The name of the Negev installation comes from the desert where the artist found the giant boulders needed for the work. The white, unevenly positioned round stones, almost three metres in diameter, invite the viewer to come between them and, by restricting visibility, squeezing the space, they somehow provoke the viewer to touch the rough surfaces, they compel direct contact. Following the spectacular impact of that installation, the artist created another monumental composition in 1988, in an open space in Seoul, Republic of Korea. Invited to the International Open Air Sculpture Symposium – a side event to the Seoul Olympic Games – she created there 10 huge, metaphorical animal heads in a composition called Space of the Dragon. In 1993, the Space of Becalmed Beings is created – a group of 40 figures of Backs cast in bronze and personally set up by the artist in the sculpture garden of the City Museum of Contemporary Art in Hiroshima. On the hill that was the last refuge of the survivors of the atomic blast, the artist placed objects that, as in Katarsis, collectively became a symbol and as it were a ritual of farewell and hope at the same time.

Abakanowicz continued to create further large-scale bronze sculptures, as well as the Incarnations series from 1985-1987. Incarnations, followed by Anonymous Portraits, are several dozen self-portraits and animal heads. From the beginning of her creative activity, Abakanowicz has asserted her unity with nature and her special relationship to trees as a sign and symbol of life and continuity. However, it was not until 1981 that she created her first works carved from tree logs entitled Trunks, followed in 1987-89 by a series named War Games, featuring symbols of life and death, strength and weakness made from fallen, hewn and abandoned tree trunks. She gives them the appearance of living beings, banding them with metal clamps, protecting them with canvas and jute, fixing them and making their existence meaningful by virtue of her attention. The constant need to explore new materials led Magdalena Abakanowicz to take on glass in her two series Sarcophagi and Glass Houses, created during her stay in France in 1983. The artist's versatile and open creative mind earned her an invitation to compete in 1991 for an urban design of extension of the grand axis of Paris at La Défense. The tree as a symbol of life was used to create the Arboreal Architecture project, extremely humanistic in its message and innovative in its engineering. Her idea envisaged the construction of monumental tree-shaped buildings, the interiors of which were to serve residential and commercial functions, while the exteriors were to become living, green structures. The concept of Arboreal Architecture was further developed, or perhaps echoed, in Hand-like Trees (1992-1993). Cast in bronze the size of natural trees, they were set up by the artist in urban spaces.

Metaphorical animal figures created at the same time as a continuation and development of the Heads series, corresponding with the human groups/herds, clearly and friendly relate to the human figures. The use of the same material seems to emphasise the unity and coherence of all co-existing living beings on earth. The artist gives the human figures animal heads, as if symbolically developing the idea of the two working together, complementing human weakness and fragility with animal strength. The power resides in unity.

Simultaneously, the sculptor continued the human theme, changing the material. Between 1990 and 1991, the Bronze Crowd was created. The artist’s last major project is Agora, a composition of 106 similarly shaped giant cast iron figures in motion forming a dynamic walking crowd. The surfaces of individual figures are reminiscent of tree bark or wrinkled skin, seemingly similar and anonymous, but different, each having its own distinct character. The group was placed in Chicago’s Grant Park.

Magdalena Abakanowicz died on 20 April 2017, leaving behind a unique body of work – a testimony to the events of the 20th century, wars, political and social abuses and, in this context, people's struggles and determination to pursue their dreams. And yet, her work has the power of a universal message, with a visionary outlook into the future, pointing to solutions and answers to humanity's most vital questions.

THE MARTA MAGDALENA ABAKANOWICZ-KOSMOWSKA AND JAN KOSMOWSKI FOUNDATION